'Yes, it’s true, it’s got my name on it, but it’s a family film,’ Martin Scorsese says, laughing down the phone from New York City just hours before boarding a plane to London. But there's a hint of exasperation in his voice too. He must be hearing this a lot. A few days after our interview, the man behind ‘Taxi Driver’ and ‘Goodfellas’ will shake hands with Prince Charles at the Royal Command Performance of ‘Hugo’, a sure sign that his new film, a 1930s-set family fantasy shot in 3D and about a Parisian orphan’s brush with early silent cinema, features no bad language, no blood and no Joe Pesci threatening to carve you into little pieces.

‘To tell the truth, I wanted to make a film that my daughter could watch,’ he explains. ‘I’m lucky I have a young daughter, she’s 12. I had daughters in my thirties and I had another at 57, and I’m a little bit older, not so youthful perhaps, but we spend pretty much every day together, and we are friends. So when I go to work I can see the world from her eyes.’

Of course, it wouldn’t be surprising if Scorsese’s daughter were more of a cinephile than most 12 year olds. Not only is her dad one of the world’s leading film directors, a man who has sustained a world-class career from ‘Mean Streets’ in the 1970s to ‘Gangs of New York’ in the new millennium, via ‘Raging Bull’ in the 1980s and ‘The Age of Innocence’ in the 1990s, but he is also a tireless propagandist for film history and world cinema. This 69-year-old Italian-American puts his name and money to film restorations, makes documentaries on past filmmakers and has now directed ‘Hugo’, a work with a celebration of silent cinema at its heart. A film for kids as well as adults, it’s intelligent and utterly free of cynicism. ‘Good, that’s what I was hoping,’ says the unmistakable voice at the other end of the line – speedy, staccato and New York to the core.

‘Hugo’ is an adaptation of Brian Selznick’s 2007 graphic novel, ‘The Invention of Hugo Cabret’, which carves a fairytale fantasy around the fact that Georges Méliès, director of 1902’s ‘Voyage to the Moon’ and one of cinema’s first dreamers and special-effects wizards, ended up working as a toyseller in Paris’s Montparnasse station when his film company collapsed at the outbreak of WWI.

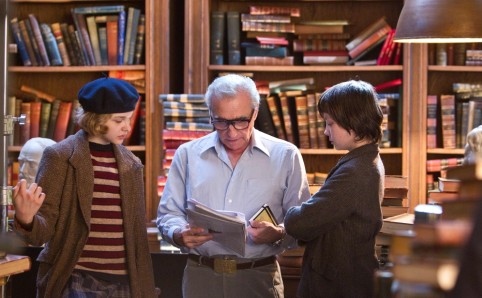

Both book and film tell of a young boy, Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield), an orphan living in the nooks and crannies of Montparnasse station who dodges a predatory station inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen) and learns from Méliès’s niece (Chloë Grace Moretz) that her uncle, the grumpy shopkeeper (Ben Kingsley), was once a filmmaker. It’s tempting to see ‘Hugo’, of all Scorsese’s films, as the one most in the tradition of Méliès: it’s built on the latest in special effects and camera technologies and, like 2010's psychological thriller ‘Shutter Island’ before it but in a very different way, it’s a film of the imagination rather than the real world.

‘I’m not so sure, I didn’t see it like that at first,’ Scorsese ponders, resisting at first the direct link between Méliès and his film. ‘For me, it was the little boy that made me want to do the film. It was his story. It was only later that people around me, people I was working with, began to draw the links between the film and my work in restoration and rediscovering filmmakers.’ One of those filmmakers was Michael Powell, who, back in the late 1970s, Scorsese brought back from the filmmaking wilderness by declaring his 1960 film ‘Peeping Tom’, which conservative critics and colleagues had damned as near-pornographic, a masterpiece. ‘It was only later on that Thelma [Schoonmaker, Scorsese’s long-term editor and Powell’s widow] pointed out the link between “Hugo” and me and Powell,’ he adds.

‘I’m not so sure, I didn’t see it like that at first,’ Scorsese ponders, resisting at first the direct link between Méliès and his film. ‘For me, it was the little boy that made me want to do the film. It was his story. It was only later that people around me, people I was working with, began to draw the links between the film and my work in restoration and rediscovering filmmakers.’ One of those filmmakers was Michael Powell, who, back in the late 1970s, Scorsese brought back from the filmmaking wilderness by declaring his 1960 film ‘Peeping Tom’, which conservative critics and colleagues had damned as near-pornographic, a masterpiece. ‘It was only later on that Thelma [Schoonmaker, Scorsese’s long-term editor and Powell’s widow] pointed out the link between “Hugo” and me and Powell,’ he adds.It’s a link that’s ongoing. This week, during his visit to London, Scorsese pitched up at BFI Southbank to introduce a pristine new version of Powell’s 1943 film ‘The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp’ – a restoration funded partly by his World Cinema Foundation. It is one of several recent events to throw a spotlight on the continuing variety and energy of Scorsese’s work. His 1978 music documentary ‘The Last Waltz’ also enjoys a re-release this week, and he even had a hand in the completion of a film by another filmmaker that comes to cinemas this week. The footage of the indie film ‘Margaret’, shot way back in 2005, was handed to Scorsese earlier this year so that he could help the director, Kenneth Lonergan (a screenwriter on ‘Gangs of New York’), find an edit of this long-gestating, troubled film with which everyone would be happy. Scorsese is not a man gearing up for retirement.

‘Yes, it’s true,’ he says when I ask if he feels more urgency to get things done now he’s almost 70. ‘You’re right, and as you say, it’s been four decades since I started out, but without wishing to underplay that, there have been struggles and times when things have not been so good and I’ve had to fight to do what I want to do.’ In his speedy, rat-a-tat voice, he highlights the making of ‘Taxi Driver’ in 1976 as a time when, two weeks into shooting, he had to stand his ground with the film’s producers and say it was either his way or the highway.

But surely he doesn’t have to fight any more? His last film, ‘Shutter Island’, took almost $300 million worldwide. He has an Oscar for ‘The Departed’. He successfully bridges art and commerce. He wins critical acclaim and he makes people lots of money. ‘I still do, I’ve always had to fight. There are times when you have to face your enemies, sit down and deal with it. But with friends it’s easier,’ he says, breaking out into the same frenzied laugh that punctuates our conversation throughout. ‘It’s better to avoid the fights in the first place, of course!’ I feel like I’ve caught a glimpse of the iron will, couched in gentility, that has kept this man at the top of his game for so long.

If there were any heated conversations about whether his new film, ‘Hugo’, should be in 3D or not, he doesn’t show it. For Scorsese, 3D is no gimmick or fad. He’s quick to point out that ‘it’s a technique with which the Lumière brothers [cinema’s French pioneers] were experimenting in the 1930s. ‘I’m walking about my rooms here while I’m talking to you, and there are artefacts to do with 3D all over the place,’ he says. ‘I’ve got 3D glasses here from various periods, and I remember going to see 3D films myself as a child in New York in the early 1950s.’

If there were any heated conversations about whether his new film, ‘Hugo’, should be in 3D or not, he doesn’t show it. For Scorsese, 3D is no gimmick or fad. He’s quick to point out that ‘it’s a technique with which the Lumière brothers [cinema’s French pioneers] were experimenting in the 1930s. ‘I’m walking about my rooms here while I’m talking to you, and there are artefacts to do with 3D all over the place,’ he says. ‘I’ve got 3D glasses here from various periods, and I remember going to see 3D films myself as a child in New York in the early 1950s.’I say that one of the moments in which the 3D is memorable in ‘Hugo’ is when the film lingers on a close-up of Ben Kingsley’s face and his head takes on an otherworldly appearance. ‘I’m glad you say that, I wanted to see what it could do for the actors and the actors’ faces.’ He jokes that one of the downsides of 3D is that it demands a bigger crew and it’s easy for someone as small as himself (he’s about five foot four) to get lost in the crowd. Did he sympathise, then, with how the little boy in ‘Hugo’ is repeatedly submerged and trampled on in busy rush-hour crowds? ‘Yes, that has happened to me before,’ Scorsese says, bursting out laughing again.

Last time I met with Scorsese, when he was in London to promote ‘Shutter Island’ early last year, he was in the middle of another epic documentary project – a history of British cinema – to add to his Bob Dylan film, ‘No Direction Home’, and his recent film about George Harrison, ‘Living in the Material World’. He says he hopes to finish the work soon. ‘I decided a long time ago not to give the documentaries a release date,’ he explains. ‘They need time to get right, especially when you’re tied to a schedule for a feature film. But I’m coming to London this week, then going to Paris, and after that I really hope that we can get it finished perhaps by about March. These projects keep me alive, they really do. It sounds dramatic, but it’s true.’ He has another feature ready to film next summer too: ‘Silence’ is an adaptation of a Shusaku Endo novel about two Portuguese priests who travel to Japan in the seventeenth century, and it will reunite Scorsese with Daniel Day-Lewis, and see him working with Benicio del Toro and Gael García Bernal for the first time. Jay Cocks, who wrote ‘The Age of Innocence’ and ‘Gangs of New York’, has penned the script.

I ask whether he finds much time to keep up with new cinema and younger filmmakers. ‘No, it’s hard to keep up,’ he begins, before launching into how much he loved the small British film ‘Archipelago’ by Joanna Hogg from earlier this year. I realise he misinterprets my question as only being about British cinema, but I let him go on. His enthusiasm is fascinating. ‘Somebody gave it to me to watch when I was filming “Hugo” and I liked the relationship it had with the landscape. I like Lynne Ramsay [the director of ‘We Need to Talk about Kevin’] too, and Andrea Arnold.’ When I mention that Arnold has just released a low-budget, defiantly auteurist version of ‘Wuthering Heights’, his ears prick up. ‘Oh, really?’

This might be a phone conversation, but I’m sure he was reaching for pen and paper. It’s an arresting image: Martin Scorsese, packing to travel to London, readying himself to premiere ‘Hugo’ in London and Paris, but scribbling down on a scrap of paper that he must remember to catch up with a radical new British version of ‘Wuthering Heights’ when – if – he ever manages to find a spare hour or two.

Hugo hits cinemas in Rio in February