If there’s one thing São Paulo doesn’t have, it’s a shortage of new bar and restaurant openings. Every week brings a flurry of press releases on the latest contenders; but the really interesting ones are few and far between. They’re the ones that get people buzzing, building up a sense of anticipation until they become the most coveted place to be in town before they’ve even opened.

With an innate ability to generate that sort of excitement – and to create the kind of buzz that lasts long after the opening party is over – the young nightlife entrepreneur Facundo Guerra is the owner or part-owner of a string of well-loved bars and clubs in São Paulo. Guerra’s latest project is the resurrection of the bar Riviera, a one-time veteran of the SP bar scene, with none other than Alex Atala on board as Guerra’s business partner – the superstar chef already owns the restaurants Dalva e Dito and D.O.M., the latter currently ranked as the world’s 4th best restaurant.

Riviera taps into a very current appetite for uncovering the city’s past: along with the art venue Pivô, which opened in a wing of Oscar Niemeyer’s Copan building in 2012, it’s one of a handful of interesting ventures that mix old and new, excavating scraps of the city’s history from the incessant destruction/construction that has turned SP into a relentlessly concrete jungle. Because in contrast with other cities, where the past is written all over the building’s façades, in São Paulo you have to dig a little deeper to find the interesting bits.

Set on one of São Paulo’s most iconic corners, Avenida Paulista and Rua da Consolação, Riviera first opened in 1949, catering to an elite crowd from the nearby neighbourhoods of Pacaembu and Higienópolis. But the bar’s chic origins soon gave way to life as a more run-of-the-mill, albeit much-loved corner bar, as changing fortunes in the surrounding area conspired to lower the tone.

An early-1970s scheme by the then-mayor, Paulo Maluf, to channel Paulista’s traffic into a tunnel under the avenue succeeded only in taking a fraction of the road underground, stranding Riviera behind a wall of traffic and cutting it off from the leafy square across the road. After a run of more than half a century, remembered with great affection by the bar’s many patrons, Riviera slid into a decline and finally closed in 2006.

|

| The corner of Paulista and Consolação, with Riviera |

Directly opposite, on the other side of Rua da Consolação, the art-house cinema Belas Artes also shut down in 2011, and despite continuing hopes that it might yet be possible to reopen the cinema, for now, it’s just a boarded-up façade. All in all, it’s not an obviously auspicious setting for a new bar.

And yet news of Riviera’s imminent revival never fails to raise curious eyebrows on paulistano faces, followed by a knowing ‘Aha,’ more often than not, when Guerra is revealed as the man behind the venture. The nightlife entrepreneur is well respected in São Paulo for being the first to open a club down on gritty Rua Augusta, better known at that time for its sleazy sex clubs than for the all-night rock’n’roll fun that goes on down there these days.

The opening of Guerra’s club, Vegas, in 2006, was instrumental in triggering a rapid revitalisation of so-called ‘Baixo Augusta’ – the area around the end of Rua Augusta closest to Centro, just a hop, skip and a jump from Riviera. A similarly rapid process of gentrification led to the closing of Vegas last year, a victim of soaring rents and a wave of property investment that has seen a handful of new residential blocks rise – with more in the pipeline – on lots that once housed carparks and strip clubs.

Other gems

The bars Volt and Z Carniceria are two of Guerra’s other business concerns nearby, as are the predominantly gay club Yacht, in Bixiga, the downtown nightclub Lions, and Cine Joia, a music venue Guerra opened in 2011 in the traditionally Japanese neighbourhood of Liberdade. Cine Joia’s transformation from an Art Deco 1950s cinema to one of the best-programmed concert venues in town is trademark Guerra style: the half-Brazilian, half-Argentinian entrepreneur has a zeitgeisty talent for blending the new with well-curated aspects of the past – he decorated Volt bar with discarded neon signs from Baixo Augusta sex clubs.

‘It’s never my intention, when I start a new business, to try and revitalise the area,’ he says when we meet one afternoon in March at a very dusty Riviera-in-progress – the interior is being totally replanned and reconstructed. ‘It would be arrogant of me to pretend that I’m doing what I do for the good of the city. I do it for my own financial well-being; and if the city benefits in some way from that, that’s great.’

The city often does benefit, and in the case of Riviera, beyond livening up the currently drab, famous intersection, there are even hopes that the existence of the new Riviera might aid the campaign for a reopened Belas Artes cinema across the road. The two are inextricably interlinked in the paulistano collective consciousness, and at the time of the closing-down of Belas Artes, when thousands of signatures were collected on petitions to keep it open, there was much talk of the old days, and of movie sessions followed by drinks over the road at Riviera.

|

| Belas Artes, as it was before closing in 2011 |

‘Riviera became popular with the film crowd in the 1970s,’ says Guerra. ‘The thing to do was to take in a movie at Belas Artes, then head over to Riviera for a beer.’ The bar was frequented by an artsy set that included filmmakers as well as MPB musicians of the likes of Chico Buarque and Elis Regina in the 1960s; and an everyday crowd of regulars, passersby and students from the nearby faculties of USP, PUC and Mackenzie universities.

‘Throughout those years, it was always a focal point for the city’s intelligentsia,’ says Guerra. During the military dictatorship that began in 1964, radicals would gather at Riviera to plot. ‘The place was a meeting point for the paulistano resistance,’ says Guerra, whose father was a communist activist during the period. ‘We’re going to create a homage to the old Riviera.’ The bar's famous red counter is referenced in its new incarnation, and Guerra is installing a wall of books above the bar: ‘Marxist books – the kinds of books you could never have had here openly in the 1960s.’

As we pick our way over the dusty concrete floor of what will soon be the main bar, stepping over bags of sand and buckets of cement, Guerra points out the spot at the back reserved for a dumb waiter, to bring Atala’s food down to the bar from the kitchen above. Upstairs, tables and chairs face a small stage: ‘Mainly for jazz,’ says Guerra, ‘but also for a guitar and a voice, or a drumkit – maybe even for somebody to do a reading.’

What kind of public do they think will come, once it opens? ‘I don’t know. It’s really hard to predict who a place will end up appealing to – you can plan for a specific kind of public, but it always ends up changing. You can try and please other people, but that way, you usually end up pleasing no one. You have to make a place that you yourself would love, and hope other people share your taste. So far, it’s worked – I’ve found a lot of people like the same kind of things I do. For Riviera, Atala and I are making the kind of bar we both know we’ll like.’

That ability to hit the nail on the head culturally is one of the secrets of his success; another is his genuine passion for São Paulo’s past and, importantly, its present. ‘We’re not trying to revive Riviera, to recreate something that’s over, from another era. This isn’t about nostalgia – it’s not about creating a vintage bar. It’s about being inspired by the past, respecting what was most important about the original Riviera, and projecting aspects of that past into the future.’

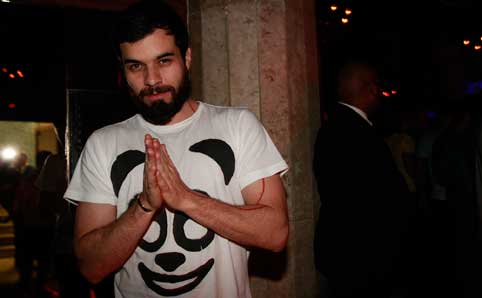

|

| Riviera |

He talks on about the history of the bar, its former owners, staff and the characters who frequented it – the people and the stories behind the bar. ‘You have to find places you have a strong relationship with, an affinity for,’ he says. ‘For me that’s part of a new business strategy. You’ve got to be thinking about a narrative when you’re starting a new bar – you need to create a story for it. No matter how good the drinks are, if it doesn’t connect with people, then people are just not going to be able to relate to it.’

He takes a swipe at the rash of looky-likey bars that throng Vila Madalena – the ‘boteco carioca’ style of bars, as he calls them, referring to the classic Rio-style street-corner bar. ‘They’re a plague here in São Paulo. Why is it that in Vila Madalena, none of the bars have any personality? Because they’re all variations on the boteco carioca or “football player” themes.’

Why make Riviera a jazz bar? ‘I was asked if I wanted to create a new nightclub,’ says Guerra, ‘but I said no: I’ve done enough of that, and São Paulo doesn’t need another club. But there are hardly any jazz clubs in São Paulo – there’s Bourbon, there’s Teta – and I do think there’s space for a really good, small jazz club, with cheap food, at around R$40.’ Atala is creating a menu that riffs on some of the dishes that were served at the old Riviera, and the plan is to open every day for lunch, running on till 2am, with live music upstairs on Thursdays, Friday and Saturday nights.

As we step outside the bar, to where traffic thunders past on Consolação, Guerra surveys the corner that road makes with the mighty Avenida Paulista. ‘São Paulo is a strange city,’ he says. ‘The only postcard image we have to offer is Paulista – a street that was once full of theatres, cinemas, bars and restaurants, and is now lined with banks! But it’s not an ugly city,’ he goes on. ‘It has layers upon layers – an accumulation of things that I think make it lovely, and a kind of misshapen quality that’s uniquely ours. But I think to really like São Paulo, you have to get past your preconceptions of beauty – past the canon of what’s supposedly beautiful. You have to have been around and seen a few things, and to have a practiced eye.’

|

Read more on the regeneration process at work in São Paulo's Centro

|