International interest in Brazilian art has become a given in recent years, thanks in part to the country’s shifting economic fortunes, and also as a result of its increasingly dynamic art scene. That’s especially true in São Paulo, where in some areas, new galleries seem to spring up with the frequency of new restaurants, with many of the galleries and the artists they represent selling works at SP-Arte 10-13 May. But though the country’s Modernist movement has generated hundreds of thousands of words of discussion over the years, writing on Brazilian contemporary art has yet to reach that kind of critical mass, especially abroad, where interest has often taken the form more of curiosity than of an informed connoisseurship.

The curator

Taking a closer interest than most, the extraordinarily well connected New York curator Neville Wakefield is in the midst of a research project into ‘emerging Brazilian art’ that he began last year at the invitation of ABACT (the Brazilian Association of Contemporary Art). Originally from the UK, Wakefield is hoping to bring the research to fruition in the form of an international exhibition encompassing the best of contemporary Brazilian art.

|

|

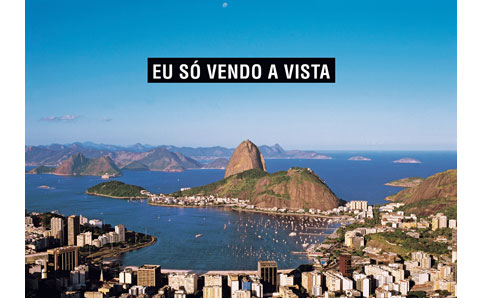

I'm Only Selling the View by Marcos Chaves |

It’s to be hoped for: Wakefield’s credentials are impressive both as an art-scene player – he counts the likes of filmmaker Larry Clark and the artist Matthew Barney amongst his New York hipster friends – and as a curator: he spent three years as part of the curatorial team at London’s Frieze art fair, and was formerly also the senior curatorial adviser at MoMA PS1, a New York contemporary art centre affiliated to the city’s Museum of Modern Art.

Brazilian artists emerge

Speaking from his home in New York, Wakefield begins, ‘I think for a lot of people, the “emergence” of this period of Brazilian art has already happened. What I’m most interested in,’ he continues, ‘is this generation of artists who are now in their late-20s or early 30s, and who are coming to the fore in an era in which there’s a slightly different version of Brazil emerging.’

|

|

Confronto by Cinthia Marcelle |

He’s still in the process of researching the content for the forthcoming exhibition – ‘It’s still hypothetical,’ Wakefield warns; but there’s one artwork that looks likely to make it into the eventual show: a piece by the artist Marcos Chaves, of Nara Roesler gallery, whom Wakefield talks about at length. Chaves’s artwork Eu so Vendo a Vista – ‘I’m Only Selling the View’ – is a picture-postcard view of Rio with those words printed across it, and it’s also the working title of the show. ‘It’s a good entry point into this show,’ says Wakefield; ‘It’s a play on the idea of seeing and selling: what we see and how we put value on it, and also on post-colonial attitudes to tourism and that kind of thing.’

Marcos Chaves, says Wakefield, is key: ‘In some ways he’s a kind of godfather of this line of art. I think his work really resonates with a younger crowd, although obviously, he’s of a different generation. There’s a performative aspect to some of what he does – sculpture in the expanded field, if you like – that’s interesting for these artists, but they’re staging things in a slightly different way: creating impediments to normal interaction or the normal flow of life and how we react to other people.’

|

|

Penelope by Tatiana Blass |

Other artists to watch

He talks on about the work being done by a whole range of Brazilian artists, covering Cintia Marcelle, Tatiana Blass and Renata Lucas by way of Marcos Chaves; plus Leandro Lima and Gisela Motta, coming-up-from-the-streets Marcelo Cidade, and young gun Paulo Nazareth. ‘But if I had to whittle it down,’ he says, ‘I’d choose Cintia Marcelle, Renata Lucas and Tatiana Blass.’ Represented by Vermelho, Luisa Strina and Millan galleries respectively, the three women share an interest, says Wakefield, in interventions in urban spaces, creating works that blend performance with sculpture, architecture and the interruption of public space, epitomising the kind of art he finds most interesting at the moment.

‘What a lot of the artists I’m interested in are doing,’ he says, ‘is playing with perceptions of space and flow and social interaction, so that whether it’s the beach in Rio or in São Paulo, there are these common social spaces that are fundamentally democratic, and that provide material for artists to make and stage artworks in daily life.’

In Confronto (‘Confrontation’), a piece by Cinthia Marcelle, the artist sets a row of fire-jugglers at a traffic lights and films the results. Two jugglers become four then six, then eight, and as the lights turn green but the performance drags on, entertainment becomes impatience becomes irritation – the film fades to black and a deafening cacophony of blaring car horns. ‘It’s about taking urban spaces as they’ve been defined by architects and by traffic,’ says Wakefield, ‘and turning what might be everyday interactions into pieces that are sculptural. The medium is the street and the encounter between people or vehicles, and the way one enters or exits the space becomes a material for this kind of art.’

|

| Falha by Renata Lucas |

He enthuses about the work of Renata Lucas, mentioning a piece, Falha (‘Failure’), in which Lucas creates a hinged, paneled floor that lifts to form a series of barriers. ‘Her work is also about a kind of social choreography and how architecture can affect that: the way people move around in space; the way they interact with one another, and the way that if you shift a door or block an entrance, it changes the flow,’ says Wakefield.

In a widely admired exhibition at SP’s Galeria Millan that ended in April 2012, the artist Tatiana Blass created an installation in the carpark in which a car appeared to be being swallowed up, sinking into the earth; and in another, Penelope, an installation at Morumbi chapel in 2011, skeins of red wool spilled through holes in the wall into the yard, unwinding away from a loom inside the church. ‘It’s not clear whether life is being unraveled within this institution,’ says Wakefield, ‘or raveled.’

Is there something especially Brazilian about all this work? ‘No, I don’t think it’s exclusively Brazilian,’ he says, ‘but I think it’s being done with a particular urgency or resonance in Brazil. I think probably the social order as well as the economic order is in a process of change there, and some of this work is about registering that change.’ Does he mean changes in terms of class, as well as in more abstract shifts? ‘Well, look, artists aren’t economists,’ he says; ‘they’re social economists, so what they’re always doing is observing the way people react with other people, particularly in public places.’