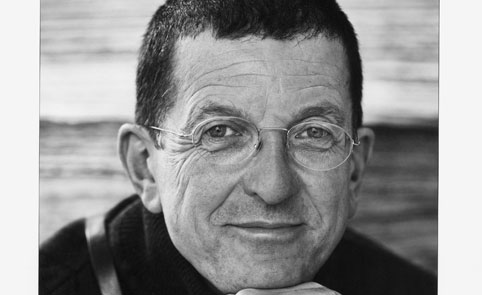

Having caused a stir in São Paulo with 'Corpos Presentes - Still Beings', Brit artist Antony Gormley gives Time Out art critic Florence Woodfield a sneak preview of the installation ‘Corpos Presentes - Still Being’ as he pieces it together in Rio three days before the opening. His first major solo show in Brazil, it includes the work 'Amazonian Field', commissioned to mark the 1992 Earth Summit. On display across São Paulo during the Rio+20 UN environmental conference in June, his work aquired even more relevance, and as he explains, the environment remains a huge influence.

You have said that your work ‘comes out of a dialogue with a place’. What’s been your dialogue with Brazil, beginning in 1992 and culminating in this major solo show 20 years later?

My dialogue with Brazil was really set by my first visit in 1992, when I flew into Manaus from Mexico City, where I had been exhibiting ‘American Field’. I flew in on a small plane, flying low over the Amazon rainforest, and then travelled upriver to Porto Velho. Porto Velho at that time was a place where every story of Brazil was present in the day-to-day life of the town - there were guns, drugs, gold and sex. My first impression was that it was totally alive.

I remember huge boats equipped with Volvo engines bringing up tons of silt and filtering it through carpet, searching for gold. It was there that I really saw the scale and diversity of the Amazon rainforest and the richness of indigenous culture. A group of 15 young artists, including Marina Abramovic, Tunga and myself had been sent to make work there. It was there that I made the work 'Amazonian Field'. The Rio 1992 climate conference was a time of real hope in terms of climate change. I remember the Tribal Parliament in the Aterro do Flamengo, where I saw Inuits talking to Kayapó Indians. They were discussing the same issues even though they were from other sides of the world. It felt like, for the first time, the voices of the exploited indigenous tribes of the world were being heard.

'Amazonian Field' came out of these experiences. It’s a conceptual work that uses a primary means to visualize a collective conscience. The issues that were being discussed in 1992 are still totally relevant today and the showing of 'Amazonian Field' in this exhibition is ironic now, given the utter failure of Rio+20. It’s as if governments and multinationals are saying that we ‘can’t afford’ to be aware that we’re cutting the branch on which we sit, when of course it’s the opposite which is true.

You’ve often used the site of the body to express the political. Often your figures stand tall and upright. Do you think that the body is the most political site of all?

Not all my bodies stand upright. Bodies can fall, and bodies can die. I also work with bodies that fall out of life. There are statistics that show that there’s currently more parts of the world at war than ever before. War has become an endemic condition that has taken hold of the daily fabric of life. In the face of this, and in the context of climate change and mass urbanization, can we usefully talk about human nature? I think not. We’re currently in a Narcissus phase, perfectly illustrated by the failure of Rio+20. We’re unable to see beyond short-term interest and have totally detached ourselves from our ecosystems. There are now huge holes in ecosystem chains, and we’re losing a species a week. We are in the sixth great extinction.

Due to the failure of politics, which has become a process of middle-management, art has become one of the last open spaces to question core beliefs and to design a viable future. Art becomes an open space where we can ask fundamental questions about ourselves. Are we an animal, or a system? If we’re a system, are we a toxic system? What can we do to change this?

I’m thinking of your statues - quiet, dark and still - cheek by jowl with the cacophony of central Rio's madness. Do you think that the presence of one of your statues (bodies) can fundamentally change a place?

A statue - in this case, a body - can change a place if it’s adequately empty and unnamed. I think of my works as thresholds, hiatuses. They are black holes in human form that invite imaginative projection in a place where there’s no room for imagination, such as the city in the form that it exists now. Cities have become places where we are controlled, by CCTV and other means, in the same way as machines are controlled. My works provide an imaginative space in which this can be challenged. It’s like opening a window in a closed room.

When I was in São Paulo recently, there was a 48-hour street party near my hotel. It was wonderful. The samba schools, performers and partygoers took over the street for the whole period. I also began to see that the other people that populated the street - homeless people and hawkers, among others - formed part of a real community who lived and went about their daily business in the street. The street has multiple uses. There is joy in this and street life becomes a celebration of all of the things that humans do.

I believe in the city as a natural human environment, but we must humanize it. It’s art that will re-define public space in the 21st Century. We can make our cities diverse, inspirational places by putting art, dance and performance in all its forms into the matrix of street life.

Your work challenges and explores how we regard and use our own bodies. Do you think that, generally, Brazilians inhabit their bodies in a different way than Europeans, for example? If so, do you think this will effect how your work is experienced here?

Being careful to avoid stereotypes, which are never useful, I think that generally Brazilians have a totally accepting attitude to their own bodies. It’s a breath of fresh air from the Cartesian mind/body division that defines European attitudes to the body. There’s a natural grace present in the everyday movements of this city, all the way from children coming home from school to beach volleyball being played until late into the night.

I feel a sense of the North when I look at your work. As a British artist, inhabitant of the Northern hemisphere, do you feel that the North, as a pole and a concept, is present in your work?

This is an enormous question. The North, and the post-reformation ethos of logical positivism has been the determining factor of agenda maps of human development. However, I think that the equator could act as a great equalizer for all life on earth, celebrated as the great energy belt of the planet. If all our energy grids were synchronized, the light side of the planet could provide energy for the dark side, according to the movement of the Sun. The power hierarchy of the world would turn on its head, as the Southern hemisphere would be a far more energy-rich place, providing energy for the North. This involves politics, of course. However, aside from this, the most important thing is that intelligence and climate should go together.

I recently worked in Alaska, and I was amazed by the intelligence and sustainability of the Tupic tribe’s relationship to their natural environment. I watched a Tupic woman weave a vest out of sea-grass that she would wear as another layer to keep her warm. I found watching her weave this ingenious fabric incredibly moving and it’s exactly this that I believe must be learned by all of us: to preserve dialogue between place, climate and human intelligence.

Aside from this, I do think that there has always been a huge attraction for the English to the polymorphous South, and I think that the English culture is good at embracing its opposite. I suppose this fascination for the South is what has brought both you and me here to Brazil.